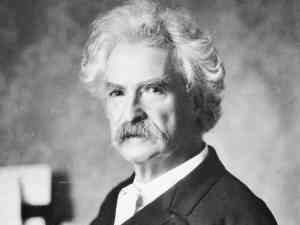

Mark Twain´s “The Story of the Good Little Boy” // “Historia de un Niño Bueno” por Mark Twain

Once there was a good little boy by the name of Jacob Blivens. He always obeyed his parents, no matter how absurd and unreasonable their demands were; and he always learned his book, and never was late at Sabbath-school. He would not play hookey, even when his sober judgement told him it was the most profitable thing he could do. None of the other boys could ever make that boy out, he acted so strangely. He woudn´t lie, no matter how convenient it was. He just said it was wrong to lie, and that was sufficient for him. And he was so honest that he was simply ridiculous. The curious ways that that Jacob had surpassed everything. He wouldn´t play marbles on Sunday, he wouldn´t rob birds´nests, he woudn´t give hot pennies to organ-grinders´monkeys; he didn´t seem to take any interest in any kind of rational amusement. So the other boys used to try to reason it out and come to an understanding of him, but they couldn´t arrive at any satisfactory conclusion. As I said before, they could only figure out a sort of vague idea that he was “afflicted”, and so they took him under their protection, and never allowed any harm to come to him.

This good little boy read all the Sunday-school books; they were his greatest delight. This was the whole secret of it. He believed in the good little boys they put in the Sunday-school books; he had every confidence in them. He longed to come across one of them alive once; but he never did. They all died before his time, maybe. Whenever he read about a particularly good one he turned over quickly to the end to see what became of him, because he wanted to travel thousands of miles and gaze on him, but it wasn´t any use; that good little boy always died in the last chapter, and there was a picture of the funeral, with all his relations and the Sunday-school children standing around the grave in pantaloons that were too short, and bonnets that were too large, and everybody crying into handkerchiefs that had as much as a yard and a half of stuff in them. He was always headed off in this way. He never could see one of those good little boys on account of his always dying in the last chapter.

Jacob had a noble ambition to be put in a Sunday-school book. He wanted to be put in, with pictures representing him gloriously declining to lie to his mother, and her weeping for joy about it; and pictures representing him standing on the doorstep giving a penny to a poor beggar-woman with six children, and telling her to spend it freely, but not to be extravagant, because extravagance is a sin; and pictures of him magnanimously refusing to tell on the bad boy who always lay in wait for him around the corner as he came from school, and welted him over the head with a lath, and then chased him home, saying, “Hi hi!” as he proceeded. That was the ambition of young Jacob Blivens. He wished to be put in a Sunday-school book. It made him feel a little uncomfortable sometimes when he reflected that the good little boys always died. He loved to live, you know, and this was the most unpleasant feature about being a Sunday-school-book boy. He knew it was not healthy to be good. He knew it was more fatal than consumption to be so supernaturally good as the boys in the books were, he knew that none of them had ever been able to stand it long, and it pained him to think that if they put him in a book he wouldn´t ever see it, or even if they did get the book out before he died it woudn´t be popular without any picture of his funeral in the back part of it. It couldn´t be much of a Sunday-school book that coudn´t tell about the advice he gave to the community when he was dying. So at last, of course, he had to make up his mind to do the best thing he could under the circumstances- to live right, and hang on as long as he could, and have his dying speech all ready when his time came.

But somehow nothing ever went right with this good little boy, nothing ever turned out with him the way it turned out with the little good boys in the books. They always had a good time, and the bad boys had the broken legs; but in his case there was a screw loose somewhere, and it all happened just the other way. When he found Jim Blake stealing apples, and went under the tree to read to him about the bad little boy who fell out of a neighbor´s apple tree and broke his arm, Jim fell out of the tree too, but he fell on him and broke his arm, and Jim wasn´t hurt at all. Jacob couldn´t understand that. There wasn´t anything in the books like it.

And once, when some bad boys pushed a blind man over in the mud, and Jacob ran to help him up and receive his blessing, the blind man did not give him any blessing at all, but whacked him over the head with his stick and said he would like to catch him shoving him again, and then pretending to help him up. This was not in accordance with any of the books. Jacob looked them all over to see.

One thing that Jacob wanted to do was to find a lame dog that hadn´t any place to stay, and was hungry and persecuted, and bring him home and pet him and have that dog´s imperishable gratitude. And at last he found one and was happy; and he brought him home and fed him, but when he was going to pet him the dog flew at him and tore all the clothes off him except those that were in front, and made a spectacle of him that was astonishing. He examined authorities, but he could not understand the matter. It was of the same breed of dogs that was in the books, but it acted very differently. Whatever this boy did he got into trouble. The very things the boys in the books got rewarded for turned out to be about the most unprofitable things he could invest in.

Once, when he was on his way to Sunday-school, he saw some bad boys starting off pleasuring in a sailboat. He was filled with consternation, because he knew from his reading that boys who went sailing on Sunday invariably got drowned. So he ran out one raft to warn them, but a log turned with him and slid him into the river. A man got him out pretty soon, and the doctor pumped the water out of him, and gave him a fresh start with his bellows, but he caught cold and lay sick abed nine weeks. But the most unaccountable thing about it was that the bad boys in the boat had a good time all day, and then reached home alive and well in the most surprising manner. Jacob Blivens said there was nothing like these things in the books. He was perfectly dumb-founded.

When he got well he was a little discouraged, but he resolved to keep on trying anyhow. He knew that so far his experiences wouldn´t do to go in a book, but he hadn´t yet reached the allotted term of life for good little boys and he hoped to be able to make a record yet if he could hold on till his time was fully up. If everything else failed he had his dying speech to fall back on.

He examined his authorities, and found that it was now time for him to go to sea as a cabin-boy. He called on a ship-captain and made his application, and when the captain asked for his recommendations he proudly drew out a tract and pointed to the word, “To Jacob Blivens, from his affectionate teacher”. But the captain was a coarse, vulgar man, and he said, “Oh, that be blowed! That wasn´t any proof that he knew how to wash dishes or handle a slush-bucket, and he guessed he didn´t want him.” This was altogether the most extraordinary thing that ever happened to Jacob in all his life. A compliment from a teacher, on a tract, had never failed to move the tenderest emotions of ship-captains, and open the way to all offices of honor and profit in their gift- it never had in any book that ever he had read. He could hardly believe his senses.

This boy always had a hard time of it. Nothing ever came out according to the authorities with him. At last, one day, when he was around hunting up bad little boys to admonish, he found a lot of them in the old iron-foundry fixing up a little joke on fourteen or fifteen dogs, which they had tied together in long procession, and were going to ornament with empty nitroglycerin cans made fast to their tails. Jacob´s heart was touched. He sat down on one of those cans (for he never minded grease when duty was before him), and he took hold of the foremost dog by the collar, and turned his reproving eye upon wicked Tom Jones. But just at that moment Alderman McWelter, full of wrath stepped in. All the boys ran away, but Jacob Blivens rose in conscious innocence and began one of those stately little Sunday-school-book speeches which always commence with “Oh, sir!” in dead opposition to the fact that no boy, good or bad, ever starts a remark with “Oh, sir”. But the alderman never waited to hear the rest. He took Jacob Blivens by the ear and turned him around, and hit him a whack in the rear with the flat of his hand; and in an instant that good little boy shot out through the roof and soared away toward the sun, with the fragments of those fifteen dogs stringing after him like the tail of a kite. And there wasn´t a sign of that alderman or that iron-foundry left on the face of the earth; and, as for young Jacob Blivens, he never got a chance to make his last dying speech after all his trouble fixing it up, unless he made it to the birds; because, although the bulk of him came down all right in a tree-top in an adjoining county, the rest of him was apportioned around among four townships, and so they had to hold five inquests on him to find out whether he was dead or not, and how it occurred. You never saw a boy scattered so*.

Thus perished the good little boy who did the best he could, but didn´t come out according to the books. Every boy who ever did as he did prospered except him. His case is truly remarkable. It will probably never be accounted for.

*This glycerin catastrophe is borrowed from a floating newspaper item, whose author´s name I would give if I knew it (M.T.)

Había una vez un niño bueno que se llamaba Jacob Blivens y que siempre obedecía a sus padres aún en las cosas mas absurdas y peregrinas y que siempre se aprendía la lección y que siempre llegaba puntual a la escuela los sábados. Nunca faltaba a clase aunque que a veces pensara que faltar era lo mejor que se podía hacer. Los demás chicos no conseguían explicarse lo que le pasaba. Se comportaba de un modo tan raro. No mentía por más que le pudiera venir bien. Se limitaba a decir que mentir estaba mal sin añadir nada más. Y era tan honrado, que resultaba simplemente ridículo. Lo extraño de su conducta era difícilmente superable. No jugaba a canicas los domingos, no iba a robar nidos de pájaros, no daba duros recalentados a los monos de los organilleros, no parecían interesarle las cosas que de verdad merecen interés. Los demás chicos se esforzaban en comprenderle pero no llegaban a ningún resultado. Sólo alcanzaban a imaginarse vagamente, como he dicho antes, que estaba «afligido», así que resolvieron protegerle y que nunca le pasara nada.

Leía este niño bueno todos los libros que en la escuela le mandaban leer los domingos. Era éste su mayor solaz y aquí radicaba todo su secreto. Creía en los niños buenos que salían en los libros de sus lecturas dominicales, confiaba absolutamente en ellos. Deseaba encontrarse alguna vez con uno en la vida real, pero nunca pudo. Todos parecían morirse antes. Cada vez que leía un libro sobre un niño bueno particularmente bueno enseguida se iba al final para ver cómo acababa su historia porque nada deseaba más que poder encontrárselo, sin importarle lo lejos que estuviera. Inútil. El niño bueno siempre se moría en el último capítulo y salía un dibujo con el funeral y todos los parientes y los chicos de la escuela dominical alrededor de la tumba en pantalones que les quedaban demasiado cortos y con gorras que les quedaban demasiado grandes y la gente secándose las lágrimas en unos pañuelos del tamaño de manteles. Siempre le cortaban el rollo de aquella misma manera: nunca pudo encontrarse con uno de esos niños buenos porque siempre se morían en el último capítulo.

Jacob albergaba la noble ambición de salir en uno de esos libros dominicales. Quería salir en uno de ellos, con dibujos en los que apareciera negándose heroicamente a mentir a su madre y a ésta llorando de alegría por ello o dando limosna a una mendiga con seis niños al salir de casa diciéndole que se lo gastara en lo que quisiera pero sin derrocharlo porque derrochar es pecado y dibujos de él negándose magnánimamente a chivarse del niño malo que inevitablemente le estaba esperando en la esquina al volver de la escuela para arrearle con un palo en la cabeza y perseguirle hasta casa gritándole “Ven aquí, ven aquí”. Esta era la ambición de Jacob Blivens. Quería salir en uno de esos libros dominicales. Le preocupaba un poco, a veces , que los niños buenos siempre acabaran muriéndose porque a él, lo que es vivir, le gustaba y era este el aspecto menos atrayente de querer convertirse en un niño de esos libros dominicales. Le constaba que ser bueno no era saludable. Le constaba que ser tan celestialmente bueno como lo eran los niños de esos libros era peor que contraer la tisis. Sabía que ninguno de ellos fue capaz de aguantar mucho y le dolía pensar que si llegaba a salir en uno de esos libros, a lo mejor nunca lo llegaba a ver o, si lo llegaban a publicar antes de que él muriese, temía que el libro no tuviera tanto éxito al faltarle el dibujo de su funeral en las últimas páginas. Si no salían las enseñanzas que al morir tenía pensado dirigir a la comunidad, difícilmente podía tratarse de un ejemplar auténtico. Al final, como es obvio, se decidió a hacer lo que en su mano estaba dadas las circunstancias: llevar una vida recta y aguantar lo que pudiera y tener ya preparado su discurso para cuando la muerte se presentara.

Pero, de alguna manera, a este niño bueno nada le salía bien, nada pasaba cómo en las historias de los niños buenos de los libros. En estos libros eran siempre los niños buenos los que se lo pasaban bien y los malos, los que se rompían las piernas, pero, en su caso, algo debía de fallar porque ocurría todo lo contrario. Cuando encontró a Jim Blake robando manzanas y se puso bajo el árbol a leerle sobre el niño malo que se cayó del manzano del vecino y se rompió la pierna, sucedió que Jim también se cayó, pero lo hizo encima de él y le rompió el brazo y a Jim no le pasó absolutamente nada. Jacob no podía comprenderlo. En los libros no pasaba eso.

En otra ocasión, después de que unos niños malos hubiesen empujado a un ciego en el barro y de que Jacob hubiese acudido a levantarle y a recibir sus bendiciones, lo que recibió en lugar de éstas fueron unos bastonazos en la cabeza y la advertencia del ciego de que más valía que no le volviera a pillar empujándole y haciendo que después le ayudaba. Esto no se correspondía con los libros y Jacob, para cerciorarse, los repasaba.

Una de las cosas que Jacob tenía pensadas era dar con un perro cojo que no tuviera dueños y anduviera hambriento y acosado y traérselo a casa y acariciarle y así contar con la gratitud eterna del perro. Y finalmente dio con uno y se alegró y se lo llevó a casa y le dio de comer pero cuando fue a acariciarle el perro se arrojó sobre él y le desgarró toda la ropa por la parte de atrás y a Jacob pero es que impresionaba verle. Consultó de nuevo sus fuentes, pero seguía sin comprender lo que pasaba. El perro era de la misma raza que la que salía en los libros pero el animal se comportó de muy distinta manera. Hiciera lo que hiciera, el muchacho se metía en problemas. Las mismas cosas por las que los niños de los libros eran recompensados, él las pagaba muy caras.

Un día, de camino a la escuela dominical, vio a unos niños que iban a disfrutar saliendo en un barco de vela. Al verles se queda perplejo porque sus lecturas le decían que los niños que salen en barco los domingos se ahogan sí o sí. Así que de la misma coge una balsa para ir a avisarles pero la balsa choca contra un tronco y Jacob se cae al río. Un hombre le saca al de poco y el doctor le bombea toda el agua fuera y le insufla dentro aire fresco con unos fuelles, pero Jacob acaba constipado y se ve obligado a guardar cama nueve semanas. Pero lo más increíble de todo es que los niños malos que estaban montados en el barco de vela se lo pasaron pipa y, sorprendentemente, volvieron a casa sanos y salvos. Jacob Blivens se decía que en los libros no podía verse nada igual. Estaba atónito.

Cuando se recuperó estaba algo desalentado pero, a pesar de ello, optó por perseverar. Sabía que sus experiencias hasta la fecha no daban para salir en ningún libro pero no había alcanzado aún el tiempo de vida que a los niños buenos se les asigna y tenía la esperanza de hacer algo que mereciera ser escrito antes de que su tiempo se consumiera. Aún cuando todo lo demás le fallase siempre le quedaban las últimas palabras que tenía pensado pronunciar.

Repasó sus fuentes y se encontró con que lo que ahora le tocaba era hacerse a la mar como grumete. Se dirigió donde un capitán marino y pidió ser enrolado y cuando el capitán le preguntó por sus referencias sacó orgullosamente unos papeles y con el dedo señaló estas palabras: “a Jacob Blivens, con afecto, de su profesor”. Solo que el capitán, siendo un tipo vulgar y poco pulido, va y le dice «que maldita la falta que le hace eso para demostrar que sabe limpiar platos o manejarse con un balde y que no se extrañe si no le necesita”. Esto fue lo más alucinante que a Jacob le había pasado jamás en su vida. Que un elogio por escrito de un profesor no suscitara en un capitán marino las más tiernas emociones y no abriera prebendas de honor y retribuciones en su estela era algo que nunca había visto ocurrir en ningún libro de los que había leído. No podía dar crédito a lo que le estaba pasando.

A este niño todo esto se le hacía duro. Nada salía nunca conforme a lo que se desprendía de sus fuentes. Al final, un día, cuando se encontraba a la búsqueda de niños malos a los que poder dirigirles sus advertencias, encontró a un puñado de ellos en una vieja fundición mientras trataban de echar unas risas a costa de catorce o quince perros colocados en fila india a los que iban a acicalar atándoles en las colas envases vacíos de nitroglicerina. A Jacob esto le llegó al alma. Se sentó encima de uno de los envases (no le importaba mancharse de grasa si el desempeño de su deber así se lo exigía), cogió del collar al perro que encabezaba la fila y clavó su mirada reprobadora en el malvado Tom Jones. Pero justo en ese momento irrumpió lleno de ira el concejal Mc Welter. Todos los niños se dieron a la fuga menos Jacob Blivens quien, consciente de su inocencia, se incorporó y púsose a declamar uno de esos imponentes discursos de los libros dominicales que siempre empezaban por “Oh, Señor” a pesar de la fatal incongruencia de que ningún niño, ni malo ni bueno, comenzaría a decir nada con «Oh, Señor». Pero el concejal, que no estaba por escuchar el resto, cogió a Jacob de la oreja, hízole darse la vuelta y le atizó en el culo con la palma de la mano saliendo el niño bueno en cuestión de segundos despedido por el tejado, escopetado hacia el sol, con los fragmentos de los quince perros tras él cual cola de una cometa. Ni del concejal ni de aquella fundición se supo que quedaran restos en la faz de la tierra. Y en lo que hace al joven Jacob Blivens se quedó sin poder compartir sus últimas palabras después de todo el tiempo que pasó preparándolas, a no ser que las compartiera con los pájaros. Porque aunque el grueso de él aterrizara sin mayores problemas en la copa de un árbol del condado vecino, el resto acabó desperdigado en cuatro municipios. Hasta cinco investigaciones se tuvieron que abrir para saber si estaba o no muerto y cómo ocurrió. Nunca antes se había dado el caso de un niño tan desperdigado.

Así pasó a mejor vida el niño bueno que, aun haciendo todo lo que estuvo en su mano, no acabó como en los libros acaban los niños buenos. A todos los niños que hicieron lo que él les fue bien, salvo a él. Su caso resulta extraordinario. Probablemente jamás sea resuelto.

La catástrofe de la glicerina está tomada prestada de un suelto de periódico, de cuyo autor diría el nombre, si lo supiera (M.T.)